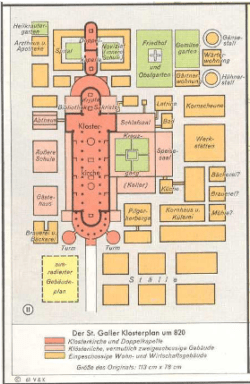

The Plan of Saint Gall (around 820) is an idealised drawing of an exemplary monastery showing various types of gardens: cloister garden, medicinal herb garden, vegetable garden and fruit garden. The latter also serves as the monastery’s cemetery. With the exception of the cloister garden, the Plan of Saint Gall reveals precise information about the plants to be grown in these gardens (cf. Schedl 2014, 123–124). What is remarkable though, is the mixed cultivation method set out in this precept. The medicinal herb garden, for example, is designed to include sage and fennel along with ornamental plants such as roses, and spices such as rosemary and pepper. The vegetable garden is intended – according to today’s understanding – to cultivate vegetables (e.g. onions and shallots) as well as spices (e.g. black cumin) and herbs (e.g. parsley and dill), whereas the orchard is not only used for native trees but also for southern fruit-bearing trees, such as the fig tree.

Particular importance is attached to the poem hortulus (around 840) written by Walahfrid Strabo (808/9-849), abbot of the monastery of Reichenau, which lists 24 medicinal plants in verse form. It is widely accepted that most plant species of the hortulus are actually cultivated (cf. Roth 2009, 50). The layout of the plants described in the hortulus is considered to be a prototype for today’s herb gardens inspired by the medieval medicinal herb gardens. It is worth noting that there are remarkable similarities with the garden layout of the Plan of Saint Gall. The raised beds that correspond to the medicinal herb garden of the Plan of Saint Gall are shown with a light background in the image on the left. The raised beds in dark grey colours host plants which, according to the Plan, are designated for the vegetable garden, whereas the yellow raised beds contain those plants that only are mentioned in the hortulus.