Gardens

Monastery gardens – more than an oasis for slowing down for tired visitors

In the tradition of the old monastic orders, the monastery garden is one of the most important facilities which as a whole make up a monastery: the church, the cloister, the monastic cells, the library, the chapter house, the guest house, the infirmary and just that garden. Its function is manifold: in addition to ensuring self-reliance and self-sufficiency, it also serves the holistic concept of monastic life. In the garden, a monk encounters the original place of longing, paradise, and through nature enters into a dialogue with the Creator. There he can also be creative in his work with the soil, plants and trees. This is how at an early stage the symbolic cloister and meditation gardens came into being. Worship in the spirit that takes place in the church, is thus complemented by working on God’s creation.

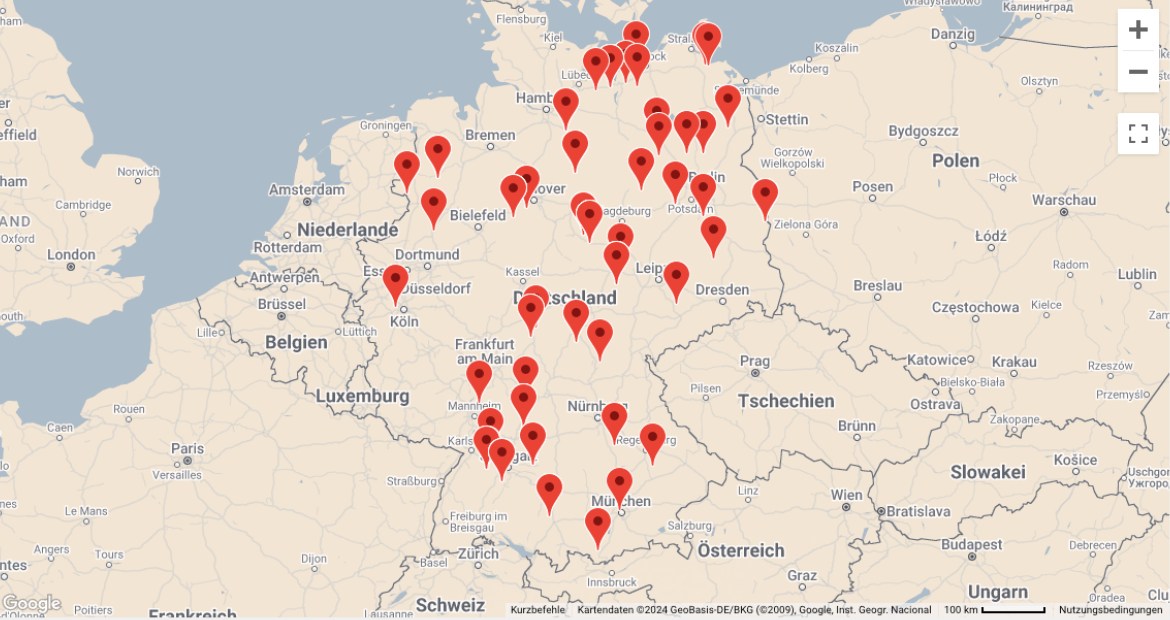

Monastery gardens have gained a new meaning, especially in our time, in the search for our position within an increasingly technical civilisation. It is still a place of longing. The diversity of monastery gardens is fascinating, regardless of whether they are historically shaped (Baroque gardens) or are currently used as show gardens or kitchen gardens (especially herb cultivation). Traditional knowledge about medicinal plants and the effects of aromas and essences is palpable in many monastery gardens. At the same time, more and more monasteries have to be closed for reasons of overageing. It is therefore all the more important to preserve the culture of monastery gardens, to document it and to make it usable in a contemporary perspective – also beyond the monastic locations, in terms of viable answers to questions of sustainability and mindfulness in dealing with our world.